It’s a hot, sunny day at the Buttermilk Trail on the south bank of the James River in Richmond.

On a walk, Laura Greenleaf, invasive plant management coordinator for the James River Parks System, easily spots some ailanthus altissima.

“Oh, here we go,” Greenleaf says. “I mean, look what it’s growing out of: pavement and pine needles.”

Ailanthus — an invasive species commonly known as tree of heaven — will grow just about anywhere it has sun. It’s good at growing in disturbed soil where other plants struggle, taking root before native species have the chance. And its roots leach toxins into the soil that discourage native plants from growing.

The tree is listed as a noxious weed in Virginia law. That means it’s illegal to transport or sell ailanthus in the commonwealth without a compliance agreement with the Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services or the federal U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Tree of heaven has long fronds, each with at least a dozen leaflets that are smooth except for one or two bumps at the base. Its trunk is skinny, and it often grows in stands of multiple trees. Female alianthus plants can sport tens of thousands of winged seeds.

Greenleaf also points out some very dead-looking ailanthus stumps — cut and treated multiple times with herbicides in a previous year — a sign of the work done to manage this invasive.

But the stumps are still monitored by volunteers.

“If you just hack at it, if you just cut it down, that just registers as an injury and it’s just a signal to grow back,” Greenleaf says.

Tree of heaven can return even if properly treated with herbicides, though not as aggressively as it otherwise would.

Sometimes dozens of sprouts can appear around a felled, untreated tree of heaven — a hydra-like survival strategy known as root suckering.

Those suckers, supported by a developed root system, can grow upwards of 10 feet in a year.

Greenleaf says the best practice is to cut a downward-sloping incision into the trunk and spray it with herbicides, leaving the tree standing — but when the trees overhang roads and walking paths, that creates a safety issue, so the task force often cuts them down.

At James River Park, most of this work is done by volunteers guided by a 2015 survey of invasives. The system does receive some grant money from state and federal programs, as well as materials from private donors and help from professional arborists.

A native defender

But what if there was another way? The herbicides are effective, although labor-intensive and accompanied by a slew of best practices to be mindful of.

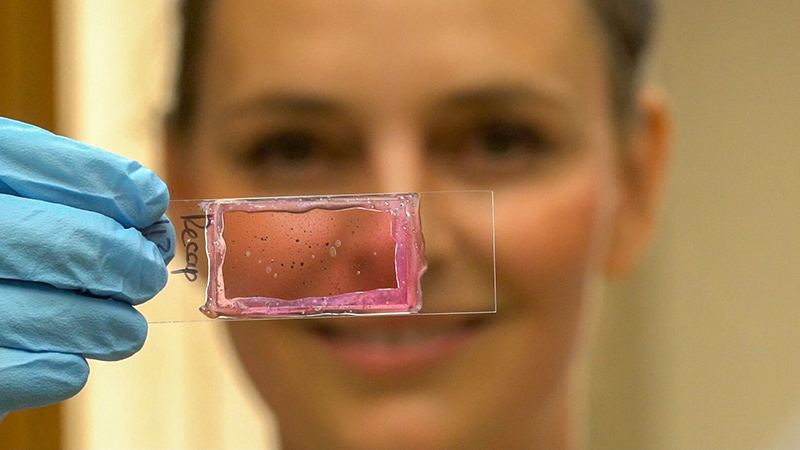

As it turns out, the answer may already be growing in Virginia forests — a fungus known as verticillium nonalfalfae.

Tim Shively, a Ph.D. student at Virginia Tech, says you just get lucky sometimes.

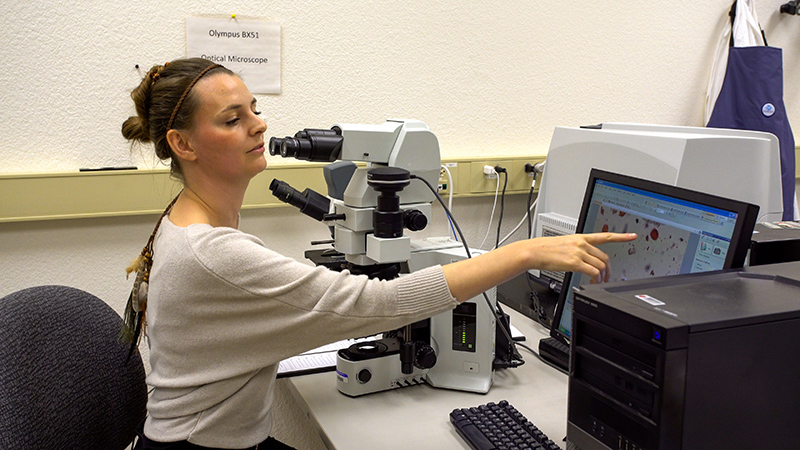

He’s studying the effects of verticillium, which causes a condition called vascular wilt in ailanthus.

“So this chokes off all the water and the nutrients from getting up into the canopy and so you actually see the trees start to wilt, the leaves will wilt, they’ll turn yellow, they’ll drop,” Shively says.

Tree of heaven rarely wins against the fungus. Shively says in field studies, verticillium has affected some native trees — but with a very low mortality rate, natives were eventually able to overtake ground where ailanthus previously grew.

And since verticillium is an organism, it doesn’t require multiple applications like herbicides because it spreads on its own.

Now, Shively’s trying to understand how the fungus functions under a wide range of circumstances. He says it’s a later stage of research to understand how it would work as a biological invasive control.

Even so, it could be years before verticillium gets market approval from the federal Animal & Plant Health Inspection Service, an agency of the USDA.

Shively says because verticillium would be used as an herbicide, it also needs Environmental Protection Agency approval. That makes the process even longer.

“Working with organisms is tricky,” Shively says — and some questions about the fungus do remain. “Do we have a reliable culture? How do we maintain its vigor and its virulence? And then what kind of formulation will be stable on the shelf and easily used by land managers in practice?”

What if you find ailanthus on your land?

Back at James River Park, Anne Wright, the lead invasive manager for a section of the Buttermilk Trail, is walking along Riverside Drive. Along the way, she identifies about a dozen young trees of heaven. They could be root suckers — or they might be from the 60-foot-tall ailanthus across the street.

“Those are huge ailanthus trees right there,” Wright says. “And that’s on private property.”

The first known introduction of ailanthus in the United States was near Philadelphia in 1784 as an ornamental plant, according to the U.S. Forest Service. It has a history of use as a shade tree in urban areas, due to its hardiness and quick-growing nature.

An unintentional consequence of that planting — like the use of english ivy as ground cover — is that the invasive has easy access to adjacent lands, including natural preserves.

Wright says if the park system’s task force employs an arborist, it can sometimes offer a discounted rate to adjacent landowners with invasives — but as long as those trees remain, they can always spread back into the park.

Landowners can also receive some help from state and local agencies.

The state Department of Forestry has instructions for a wide range of management techniques. The department has also worked with universities and woodworkers to investigate value-added uses for ailanthus lumber, in an effort to encourage more harvesting and offset control costs — it shows some promise as pulpwood, firewood, or charcoal, but ailanthus wood is often not suitable for construction and woodworking.

Local cooperative extensions, which offer resources from Virginia Tech and Virginia State University across the commonwealth, sometimes have info too. When asked for information, an employee of the Richmond extension said they couldn’t directly help, as the extension no longer has an agricultural agent — but referred VPM News to Chesterfield County’s extension, which does provide information.

Why should we care about tree of heaven?

These are fast-growing trees in a city that’s trying to expand tree canopy, not decrease it.

We have to look at the core problem of invasives, says Greenleaf. They don’t add much to or benefit the land, all while outcompeting helpful species that exist in a native, interdependent ecosystem.

“You don’t have abundant, diverse wildlife without native flora and healthy native plant communities,” Greenleaf says.

Ultimately, invasive plant species like ailanthus are so ubiquitous that eradicating them from invaded areas would require a universal effort across state and federal governments. It would take decades, cost huge amounts and might not even succeed.

“It’s really more management at the places you care about,” says Kevin Heffernan, stewardship biologist for the state Department of Conservation and Recreation.

That might include natural areas like James River Parks, which draw visitors by offering a connection to native plants and wildlife. Management can also be done to protect infrastructure.

There is no one-size-fits-all approach to invasive management, but centralized planning can help.

The Virginia Invasive Species Management Plan outlines what powers state agencies have to control invasives today and strategies to further protect native ecosystems.

The state budget, recently agreed upon by General Assembly members and Gov. Glenn Youngkin, includes some new funding to implement that plan. In all, legislators approved $4.9 million over the next two fiscal years to increase staffing at several state agencies and support the development of Partnerships for Regional Invasive Species Management, or PRISMs. (Virginia’s fiscal year from July 1 through June 30.)

One of those partnerships exists already: The Blue Ridge PRISM sets a framework for public and private groups and individuals to manage invasives.

Other measures to slow the spread of invasives were vetoed by Youngkin, however. Del. Holly Seibold’s (D–Fairfax) bill to require plant sellers to label species on the state invasives list was cut down by the governor.

Del. Paul Krizek’s (D–Fairfax)bill to authorize local ordinances banning the sale of English ivy — a groundcover plant that rapidly spreads across the ground and into the tree canopy, blocking sun and weighing down branches — was also vetoed.

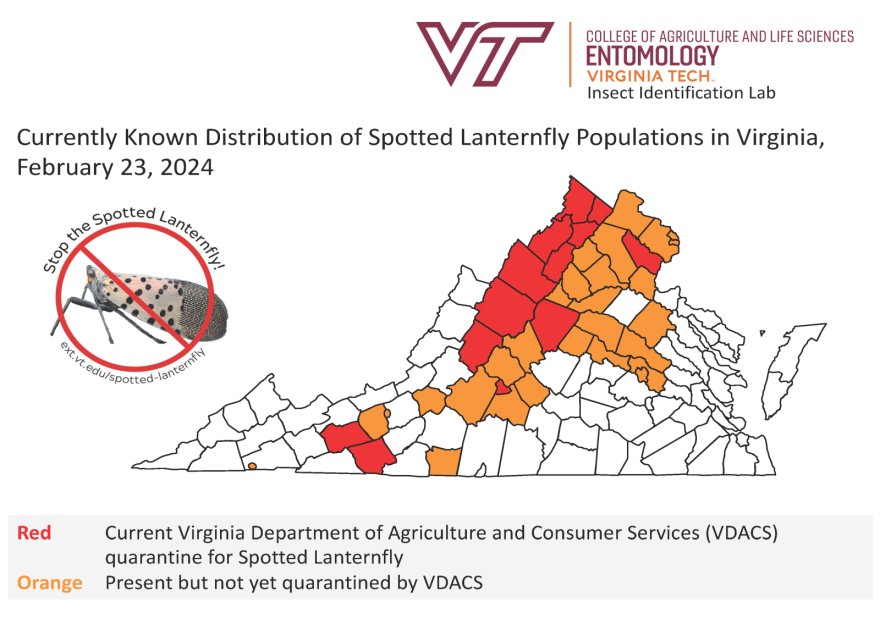

Tree of heaven is a preferred host of another infamous invasive — the spotted lanternfly. The species are native in the same parts of Asia.

“In some kind of weird love story, they found each other on the other side of the globe,” Shively says.

The critters probably reached North America about a decade ago, making headlines for their threat to agriculture: Spotted lanternflies will swarm on crops, smothering them.

The agriculture-destroying critters have spread across 17 states since their likely arrival, taking advantage of host species’ ability to overtake disturbed, sunny soil — like you might find on the side of a roadway.

Next time you see a stand of ailanthus by the highway, that’s basically a lanternfly motel. Our highways are their highways.

The Virginia Department of Transportation told VPM News it collaborates with VDACS and other state agencies to control lanternflies and tree of heaven, but its No. 1 priority is protecting infrastructure and drivers.

And with more than 57,000 miles of roads to worry about, the problem’s scale is huge for a state agency. Actually managing the full extent would require much more funding and public interest.

VDACS has the authority to implement quarantines on certain species — and has one in place for spotted lanternfly. Richmond is not under a lanternfly quarantine, but there have been reported sightings within city limits.

Supporting native wildlife

As we approach the end of our walk on Riverside Drive, evidence of Wright’s good work comes into view.

A zebra swallowtail butterfly flutters around us: It uses the native pawpaw as a host. In areas that used to be covered by English ivy, ailanthus and other invasives, pawpaws now have room to grow.

“So there you’ve got the plant and the user,” Wright says.

Invasive management at the James River Parks System is ongoing.

(Matt McClain/The Washington Post)

(Matt McClain/The Washington Post)